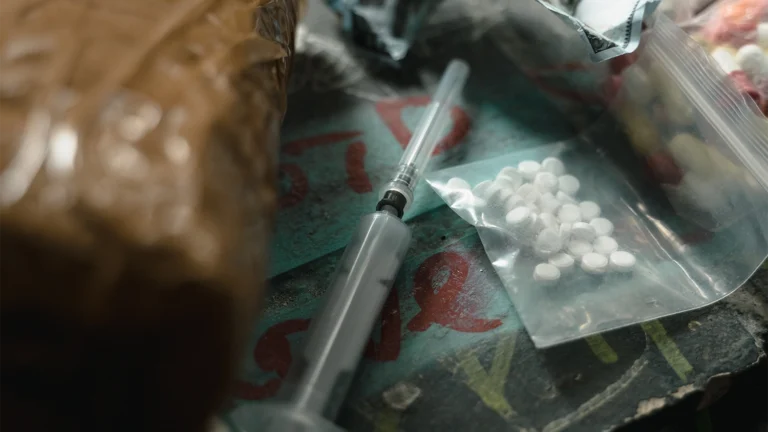

GUEST COLUMN: Fentanyl crisis needs stronger legislation

Colorado is in the midst of an epidemic, and the fight against fentanyl is truly life and death. Since 2015, Colorado has suffered 1,578 fentanyl…

Colorado is in the midst of an epidemic, and the fight against fentanyl is truly life and death. Since 2015, Colorado has suffered 1,578 fentanyl…

Colorado’s public option proposal is the most extreme yet. Starting next year, all private insurers will have to offer a standardized plan subject to rules set by…